- Charles the Bald

- (823-877)Carolingian king and emperor, Charles the Bald reigned during a time of great unrest for the Carolingian Empire. As fourth son of Louis the Pious and only son of Louis with his second wife Judith, Charles was forced to endure the challenges of his brothers to his father's authority and to his own legitimate rights of inheritance. After his father's death, Charles faced the rivalry of his brothers and participated in a terrible civil war that led to the division of the empire among Louis's three surviving sons. Charles came to rule the western part of the kingdom, the region that later became France. Although Charles did not receive the imperial title at the division of the empire, he actively sought after it and laid claim to it in 875. His pursuit of the imperial title was, in part, the result of his devotion to the memory of his grandfather, Charlemagne, and the greatness of his reign. Charles, like his grandfather, actively promoted cultural life in the kingdom and was the friend and patron of some of the most important scholars of the Carolingian Renaissance, including Hincmar of Rheims, Rabanus Maurus, and John Scotus Erigena.

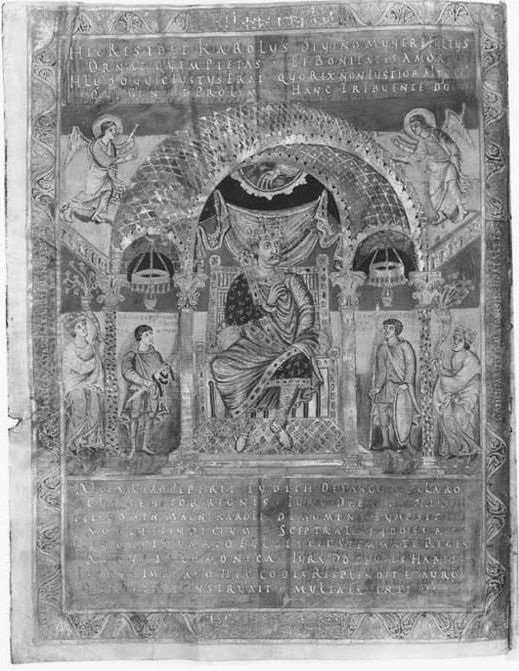

Iluminated manuscript page of Charles the Bald enthroned (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich)The birth of Charles the Bald in 823 was met with great joy, but also with some consternation because of the questions it raised about the succession to the throne after his father's death. Several years earlier, in 817, Louis the Pious had held a great council of the leading churchmen and nobles of the empire to determine the matter of the succession. He devised a system in which the realm was divided between his three sons, with the eldest, Lothar, recognized as co-emperor and, eventually, sole emperor. Louis's other two sons, Louis the German and Pippin, were made sub-kings and were granted authority within their own kingdoms but were subject to Louis and then Lothar. The birth of Charles complicated this settlement, a problem made worse because many believed that the settlement was divinely inspired and to undo it would be an offense against God. But this is precisely, under the influence of his wife Judith, what Louis did in the late 820s, with the consequence being revolts of his older sons in 830 and 833-834. During both revolts, Charles was packed off to a monastery, where he was to remain without claim to his inheritance. Charles was rescued both times by his father, who managed to regain, after some difficulty, control of the empire on both occasions. In 837 Charles was granted as his inheritance a sizeable kingdom that included much of modern France. In the following year, after the death of Charles's brother Pippin, Louis disinherited Pippin's sons and granted Aquitaine to his youngest son. Charles also benefited from the reconciliation his father made with Lothar, who had been Charles's godfather, and as a result Lothar and Charles forged an alliance in their father's last year.After the death of Louis the Pious in 840, the alliances forged by Louis broke down, and the empire fell into civil war. Lothar, who had promised to protect Charles, now turned against him in an effort to take control of the entire empire. Charles quickly turned to his other brother, Louis the German, to forge an alliance against their mutual foe, and for the next three years the three brothers fought for control of the empire. In 841, Charles and Louis inflicted a stinging defeat on Lothar at the Battle of Fontenoy, which Nithard, the chronicler of the civil wars, notes was interpreted as God's judgment against Lothar, delivered by Charles and Louis. Firm in their conviction that God was on their side, and in the face of Lothar's continuing attempts to draw Charles away from Louis, Charles and Louis swore an oath to one another in 842. The so-called Oath of Strasbourg was an important moment in the civil wars, but important also because it contains the first recorded examples of the Romance and Germanic languages. The alliance held, and in 843, Lothar submitted and the three brothers accepted the Treaty of Verdun, which assigned the western kingdom to Charles; the eastern kingdom to Louis; and the central kingdom, Italy, and the imperial title to Lothar.Over the next two decades and more Charles was involved in continued conflict with his brothers for preeminence in the empire and with the sons of Pippin for control of the west Frankish kingdom. In an effort to safeguard his position in his kingdom, Charles held a council in Coulaines, near Le Mans, in 843, in which he promised to protect the property of the church and the nobility and to secure peace and justice in the realm in exchange for the aid and counsel of the nobility. This was an important step in the relations of the king and nobles, in which Charles sought to establish a reciprocal working relationship. Although he was not always successful, Charles restructured government and administration in his kingdom in meaningful ways. Of course, he did not always have the support of the nobility, but Charles did manage to secure some support for his authority despite the nobility's ambitions. Notably, in Aquitaine he managed to find support despite local patriotism and support for the heirs of Pippin. Indeed, one of Louis the Pious's former allies now struggled against Charles, but because of some local support Charles was able to defeat him and also Pippin's heir. But, like his grandfather before him, Charles was forced to recognize Aquitainian uniqueness, and he appointed his son, Charles the Child, king of Aquitaine. Moreover, although he had only mixed support from the nobility, Charles could count on the full support of the church in his kingdom, particularly from the indomitable bishop, Hincmar of Rheims. The church and bishops played a critical role in preserving Charles's authority in the face of invasion by his brother Louis the German in 858.Relations with his brothers ebbed and flowed after the treaty of Verdun. At times, relations were better with Lothar and at others better with Louis the German. Indeed, warming relations between Lothar and Charles may have precipitated the invasion by Louis in 858. There were also examples, however, of cooperation between the three, best exemplified in the meeting at Meerssen in 847 to respond to the assaults by the Northmen. But as Charles became increasingly secure in his kingdom, and his brothers and nephews became less of a threat, Charles turned his attention to the kingdom of his nephew Lothar II, son of the emperor Lothar. Particularly after 860, Charles was in a position to expand his authority at the expense of his brothers. He was interested in the dynastic problems of his older brother's son and successor, who was unable to provide an heir or to gain the divorce he desired, and in 862, Charles and Louis agreed to share their nephew's territory, Lotharingian, on Lothar II's death. In 870, the year after Lothar's death, Louis and Charles signed the Treaty of Meerssen, in which they agreed to share their nephew's kingdom and ignored the claims of Louis II, the emperor who ruled in Italy. In 872, Pope Hadrian II wrote to Charles and expressed his support for the king's claim to the imperial title. Indeed, Charles's ambitions grew as his control of the west Frankish kingdom increased.Seeking to expand his authority and resurrect the glory of his grandfather Charlemagne, Charles awaited the proper moment. When Louis II died without an heir in 875, Charles seized the opportunity to become emperor, and on Christmas day of that year he was crowned by the pope, John VIII, in Rome. He was opposed by Louis the German, who sent troops to impede Charles's progress in Italy and invaded the western Frankish kingdom. Once again, Charles was saved by Hincmar and returned secure in his kingdom. Charles clearly intended to rule the entire empire, not just his kingdom, after the coronation. After the death of Louis the German in 876, Charles marched into Lothar's old kingdom to take control of Aachen, the imperial capital. He also threatened to invade the eastern Frankish kingdom of his late brother Louis, but became ill and was easily repulsed by the new king, his nephew Louis the Younger. Despite this setback, Charles remained dedicated to the imperial ideal and his responsibilities as emperor, and thus willingly accepted a call by the pope to come to the defense of Rome.Preparing for his departure, Charles held a council at Quierzy in 877, and his proclamations at the council have long been seen as a concession to the nobility and the confirmation of the rights of hereditary succession. The capitulary of Quierzy, however, was intended to strengthen royal authority by reinforcing the king's right to recognize the successor to the office of count. He departed for Italy soon after the council but was forced to return when he learned of a revolt by the nobility and the invasion by Carloman, the eldest son of Louis the German. Worn out by overexertion, Charles died on his return to the kingdom on October 6, 877. Although his reign as emperor was short and tumultuous, Charles was one of the great Carolingian kings and a worthy heir of his namesake Charlemagne.See alsoCarolingian Dynasty; Charlemagne; Fontenoy, Battle of; Judith; Lothar; Louis the German; Louis the Pious; Nithard; Strasbourg, Oath of; Verdun, Treaty ofBibliography♦ Gibson, Margaret, and Janet Nelson, eds. Charles the Bald: Court and Kingdom. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1981.♦ Laistner, Max L. W. Thought and Letters in Western Europe, a.d. 500 to 900. 2d ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1976.♦ McKitterick, Rosamond. The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751-987. London: Longman, 1983.♦ Nelson, Janet. Charles the Bald London: Longman, 1992.♦ Riché, Pierre. The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Trans Michael Idomir Allen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.♦ Scholz, Bernhard Walter, trans. Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Iluminated manuscript page of Charles the Bald enthroned (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich)The birth of Charles the Bald in 823 was met with great joy, but also with some consternation because of the questions it raised about the succession to the throne after his father's death. Several years earlier, in 817, Louis the Pious had held a great council of the leading churchmen and nobles of the empire to determine the matter of the succession. He devised a system in which the realm was divided between his three sons, with the eldest, Lothar, recognized as co-emperor and, eventually, sole emperor. Louis's other two sons, Louis the German and Pippin, were made sub-kings and were granted authority within their own kingdoms but were subject to Louis and then Lothar. The birth of Charles complicated this settlement, a problem made worse because many believed that the settlement was divinely inspired and to undo it would be an offense against God. But this is precisely, under the influence of his wife Judith, what Louis did in the late 820s, with the consequence being revolts of his older sons in 830 and 833-834. During both revolts, Charles was packed off to a monastery, where he was to remain without claim to his inheritance. Charles was rescued both times by his father, who managed to regain, after some difficulty, control of the empire on both occasions. In 837 Charles was granted as his inheritance a sizeable kingdom that included much of modern France. In the following year, after the death of Charles's brother Pippin, Louis disinherited Pippin's sons and granted Aquitaine to his youngest son. Charles also benefited from the reconciliation his father made with Lothar, who had been Charles's godfather, and as a result Lothar and Charles forged an alliance in their father's last year.After the death of Louis the Pious in 840, the alliances forged by Louis broke down, and the empire fell into civil war. Lothar, who had promised to protect Charles, now turned against him in an effort to take control of the entire empire. Charles quickly turned to his other brother, Louis the German, to forge an alliance against their mutual foe, and for the next three years the three brothers fought for control of the empire. In 841, Charles and Louis inflicted a stinging defeat on Lothar at the Battle of Fontenoy, which Nithard, the chronicler of the civil wars, notes was interpreted as God's judgment against Lothar, delivered by Charles and Louis. Firm in their conviction that God was on their side, and in the face of Lothar's continuing attempts to draw Charles away from Louis, Charles and Louis swore an oath to one another in 842. The so-called Oath of Strasbourg was an important moment in the civil wars, but important also because it contains the first recorded examples of the Romance and Germanic languages. The alliance held, and in 843, Lothar submitted and the three brothers accepted the Treaty of Verdun, which assigned the western kingdom to Charles; the eastern kingdom to Louis; and the central kingdom, Italy, and the imperial title to Lothar.Over the next two decades and more Charles was involved in continued conflict with his brothers for preeminence in the empire and with the sons of Pippin for control of the west Frankish kingdom. In an effort to safeguard his position in his kingdom, Charles held a council in Coulaines, near Le Mans, in 843, in which he promised to protect the property of the church and the nobility and to secure peace and justice in the realm in exchange for the aid and counsel of the nobility. This was an important step in the relations of the king and nobles, in which Charles sought to establish a reciprocal working relationship. Although he was not always successful, Charles restructured government and administration in his kingdom in meaningful ways. Of course, he did not always have the support of the nobility, but Charles did manage to secure some support for his authority despite the nobility's ambitions. Notably, in Aquitaine he managed to find support despite local patriotism and support for the heirs of Pippin. Indeed, one of Louis the Pious's former allies now struggled against Charles, but because of some local support Charles was able to defeat him and also Pippin's heir. But, like his grandfather before him, Charles was forced to recognize Aquitainian uniqueness, and he appointed his son, Charles the Child, king of Aquitaine. Moreover, although he had only mixed support from the nobility, Charles could count on the full support of the church in his kingdom, particularly from the indomitable bishop, Hincmar of Rheims. The church and bishops played a critical role in preserving Charles's authority in the face of invasion by his brother Louis the German in 858.Relations with his brothers ebbed and flowed after the treaty of Verdun. At times, relations were better with Lothar and at others better with Louis the German. Indeed, warming relations between Lothar and Charles may have precipitated the invasion by Louis in 858. There were also examples, however, of cooperation between the three, best exemplified in the meeting at Meerssen in 847 to respond to the assaults by the Northmen. But as Charles became increasingly secure in his kingdom, and his brothers and nephews became less of a threat, Charles turned his attention to the kingdom of his nephew Lothar II, son of the emperor Lothar. Particularly after 860, Charles was in a position to expand his authority at the expense of his brothers. He was interested in the dynastic problems of his older brother's son and successor, who was unable to provide an heir or to gain the divorce he desired, and in 862, Charles and Louis agreed to share their nephew's territory, Lotharingian, on Lothar II's death. In 870, the year after Lothar's death, Louis and Charles signed the Treaty of Meerssen, in which they agreed to share their nephew's kingdom and ignored the claims of Louis II, the emperor who ruled in Italy. In 872, Pope Hadrian II wrote to Charles and expressed his support for the king's claim to the imperial title. Indeed, Charles's ambitions grew as his control of the west Frankish kingdom increased.Seeking to expand his authority and resurrect the glory of his grandfather Charlemagne, Charles awaited the proper moment. When Louis II died without an heir in 875, Charles seized the opportunity to become emperor, and on Christmas day of that year he was crowned by the pope, John VIII, in Rome. He was opposed by Louis the German, who sent troops to impede Charles's progress in Italy and invaded the western Frankish kingdom. Once again, Charles was saved by Hincmar and returned secure in his kingdom. Charles clearly intended to rule the entire empire, not just his kingdom, after the coronation. After the death of Louis the German in 876, Charles marched into Lothar's old kingdom to take control of Aachen, the imperial capital. He also threatened to invade the eastern Frankish kingdom of his late brother Louis, but became ill and was easily repulsed by the new king, his nephew Louis the Younger. Despite this setback, Charles remained dedicated to the imperial ideal and his responsibilities as emperor, and thus willingly accepted a call by the pope to come to the defense of Rome.Preparing for his departure, Charles held a council at Quierzy in 877, and his proclamations at the council have long been seen as a concession to the nobility and the confirmation of the rights of hereditary succession. The capitulary of Quierzy, however, was intended to strengthen royal authority by reinforcing the king's right to recognize the successor to the office of count. He departed for Italy soon after the council but was forced to return when he learned of a revolt by the nobility and the invasion by Carloman, the eldest son of Louis the German. Worn out by overexertion, Charles died on his return to the kingdom on October 6, 877. Although his reign as emperor was short and tumultuous, Charles was one of the great Carolingian kings and a worthy heir of his namesake Charlemagne.See alsoCarolingian Dynasty; Charlemagne; Fontenoy, Battle of; Judith; Lothar; Louis the German; Louis the Pious; Nithard; Strasbourg, Oath of; Verdun, Treaty ofBibliography♦ Gibson, Margaret, and Janet Nelson, eds. Charles the Bald: Court and Kingdom. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1981.♦ Laistner, Max L. W. Thought and Letters in Western Europe, a.d. 500 to 900. 2d ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1976.♦ McKitterick, Rosamond. The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751-987. London: Longman, 1983.♦ Nelson, Janet. Charles the Bald London: Longman, 1992.♦ Riché, Pierre. The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Trans Michael Idomir Allen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.♦ Scholz, Bernhard Walter, trans. Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe. 2014.